Like most poor women in African nations, the majority of Maasai women in Kenya are destined to live a life of poverty and cultural oppression. Just one generation ago, less than 20 percent of Maasai women in Kenya enrolled in school. Today, even with free primary school education in Kenya since January 2003, only 48 percent of Maasai girls enroll in school, and only 10 percent of girls make it to secondary school.

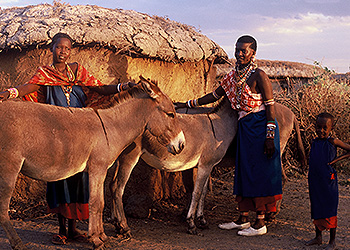

Typically, Maasai girls are circumcised between the ages of 11 to 13 and soon afterwards married to a man chosen by her father in exchange for cattle and cash. A Maasai woman will never be allowed to divorce, except in the most egregious cases of physical abuse, and will never be allowed to marry again, even if the husband her father chooses is an old man who dies when she is still in her teens. Instead, she becomes the property of one of her husband’s brothers. She will be one of multiple wives, and will have many children, regardless of her health or ability to provide for them. She will rise early every day to milk cows, and spend her days walking miles to water holes to launder clothes and get water, and to gather heavy loads of firewood to carry back home. If she is lucky, she will have a donkey to share her burden. She will live a life of few physical comforts, dependent on a husband and a family she did not choose. Her life expectancy is 45 years.

Typically, Maasai girls are circumcised between the ages of 11 to 13 and soon afterwards married to a man chosen by her father in exchange for cattle and cash. A Maasai woman will never be allowed to divorce, except in the most egregious cases of physical abuse, and will never be allowed to marry again, even if the husband her father chooses is an old man who dies when she is still in her teens. Instead, she becomes the property of one of her husband’s brothers. She will be one of multiple wives, and will have many children, regardless of her health or ability to provide for them. She will rise early every day to milk cows, and spend her days walking miles to water holes to launder clothes and get water, and to gather heavy loads of firewood to carry back home. If she is lucky, she will have a donkey to share her burden. She will live a life of few physical comforts, dependent on a husband and a family she did not choose. Her life expectancy is 45 years.

If you educate a woman: She will know her rights and have the confidence and independence to stand up for them. She will choose whom to marry and when to marry. She will have fewer children, and they will be healthier and better educated than the previous generation. She will not circumcise her daughters. She will have economic security. She will spend 90 percent of her income on her family, compared to 35 percent that an educated man would spend. She will help support her parents. She will not forget where she came from.

But the cultural pressures against women’s education are nothing short of overwhelming.

But the cultural pressures against women’s education are nothing short of overwhelming.

The Maasai are one of the most impoverished tribes in East Africa. A noble and dignified people, they have proudly mantained their traditional lifestyle and cultural identity despite pressures of the modern world. They live a nomadic lifestyle raising cattle and goats, wearing traditional clothes, and living in small villages called manyattas, which are circular arrangements of mud huts. But increasing land acquisition throughout Kenya’s Maasailand is threatening their nomadic culture, and pressure to accept change is growing. With this pressure comes a more urgent need to educate the current generation of boys and girls. In the process of preserving their culture, however, the Maasai have embraced a system that denies women basic human rights: the right to an education; the right to control her body, the right to choose whom and when to marry, the right to express an opinion.

Barriers To Education

Maasai girls must face many obstacles to get an education, and most of those are related to the high level of poverty among the Maasai. The cost of education is prohibitive for most families, and the promise of a dowry is a powerful incentive for arranging a daughter’s marriage as soon as she “crosses the childhood bridge.” But cultural factors also contribute to preventing girls from getting and education.

Maasai girls must face many obstacles to get an education, and most of those are related to the high level of poverty among the Maasai. The cost of education is prohibitive for most families, and the promise of a dowry is a powerful incentive for arranging a daughter’s marriage as soon as she “crosses the childhood bridge.” But cultural factors also contribute to preventing girls from getting and education.

Economic, Cultural & Physical Barriers

The economic, cultural and physical factors that combine to deny education to Maasai girls in Kenya are numerous and, taken together, almost impossible for all but the most determined girls to overcome. Even when possible, Maasai girls have the added impediment of cultural beliefs that prevent many from enrolling or completing school.

They include:

- Economic incentives for early marriage, such as cattle and cash dowries

- The belief that the biological family does not benefit from educating a daughter, since the girl becomes a member of her husband’s family when she marries, and they will reap the benefits

- Family and peer pressure for early marriage, as women are valued by the number of children they have

- Fear of early pregnancy, which is a disgrace prior to marriage and lowers the bride price, which perpetuates the practice of early marriage,

and finally - The distances that a girl must walk to the nearest school make it unsafe, and even impossible for a nursery-school-age child

Cost of Education

Maasai girls who do enroll in primary school attend public day schools which are free. But all students in Kenya are required to wear uniforms, and many families cannot afford even the uniform needed for their child to go to school. Public primary boarding schools, which offer many advantages, are prohibitively expensive for most Maasai families. The quality of education in these rural day schools is rarely adequate to prepare students for the national tests, which are required to go on to secondary school, because these schools are underfunded and woefully overcrowded, with a student-teacher ratio as high as 100 to 1.

For the exceptional girl who does pass the national test to graduate from primary school, all secondary schools in Kenya are boarding schools, and the annual cost is prohibitive for most Maasai but, if economically feasible, sons are always given priority.

Economic Barriers Unrelated to the Cost of Education

Economic incentives for early marriage. A daughter’s marriage increases the wealth of Maasai girl’s family through combined cattle and cash dowries and, since a girl joins her husband’s family upon marriage, her father is relieved of the economic burden of supporting her. The practice of early marriage is also worsened by the increasing poverty of the Maasai people, which leads Maasai fathers to marry their daughters off at increasingly young ages.

Return on investment. For those few families that are able to pay education costs, there is a widespread cultural preference for educating sons first. This stems from the tradition that Maasai girls leave their parents’ village and become a member of the husband’s family upon marriage. Maasai fathers tend, therefore, to believe that their family will not benefit from investing in their daughter’s education.

Cultural Barriers

Family and peer pressure for early marriage. Early marriage is the most often cited reason that Maasai girls drop out of school. Maasai girls are taught that circumcision is a rite of passage into womanhood that accompanies puberty and an immediate precursor to marriage. Once circumcised, they are ridiculed by their peers if they continue their education, since school is for children. Further escalating the pressure for early marriage is the reality that in the Maasai culture women are traditionally valued on the basis of how many children they can produce for their husbands, not by how educated or economically successful they might become.

Fear of early pregnancy. Pregnancy is the second most frequent reason that girls drop out of school. In the Maasai culture, children as young as nine years old are not allowed to stay in the same house with their father, and instead sleep in a separate house without supervision. In addition, girls are not told how a woman becomes pregnant. This combined lack of supervision and ignorance make girls highly vulnerable to becoming pregnant, and pregnancy before marriage brings disgrace and a reduced bride price. Fear of premarital pregnancy is a common reason for parents to insist that their daughters leave school and marry early.

Physical Barriers

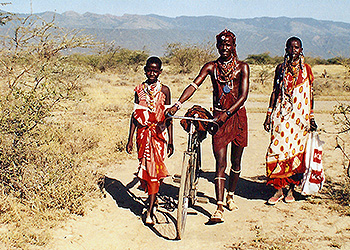

Walking distance to school. Since the pastoral Maasai require significant land resources to graze their cattle, their villages are constructed far apart from each other. As a result, one school must serve several villages typically within a 15- to 20-kilometer radius. There are no cars, buses, horses, or even bicycles available to Maasai children, so they must walk this great distance. Many girls are denied an education solely because of parental concerns for their safety during these long walks.

Even for those who make it to school, the long walks undermine education. Not surprisingly, teachers report that children who have spent two to five hours walking to school in the morning, often without having had anything to eat, are tired, and their ability to concentrate is impaired. Also, it is often late when children arrive home after such long walks, and they are still required to do chores. Even if they still have the desire and energy to study after they are finished with their responsibilities at home, it is dark and there is no electricity or artificial light.

The nomadic Maasai lifestyle. The Maasai are a pastoral, nomadic society, and circumstances sometimes require that families move in order to find water and grass for their cattle. In drought conditions, a child’s education is often interrupted or halted until the rains come, causing them to fall behind in their school work, or to stop attending school altogether.